Art Sunday 09/21/08: My Trip to MOMA

The Dancers (I) Oil on canvas Henri Matisse The Museum of Modorn Art New York City

The highlights of what I saw:

French painter Henri Matisse (1869 – 1954) is best known for his paintings and collages, and as the founder of Fauvism, a style of painting that focused on using color to express emotion, rather than represent the actual/natural colors of the subject of the painting. Matisse’s fame and significance in modern art is probably only matched by his good friend and rival, Pablo Picasso.

Matisse was born in Le Cateau-Cambrésis, Nord-Pas-de-Calais, France, and was raised in Bohain-en-Vermandois, where his family owned a seed business. Matisse never painted until he was twenty, and only because his mother bought him a set of paints to keep him occupied during his recovery from appendicitis. Until that incident, Matisse was on track to study law, but soon switched to art, enrolling in the Académie Julian in 1891.

In 1905, Matisse and several other artists (including André Derain and Georges Braque) exhibited a style of painting that used color wildly and unrealistically, earning them the title of ‘wild beasts’ – Fauves – and starting the Fauvist movement. The Fauvist movement lasted less than a year, and Matisse moved on to produce his most significant works.

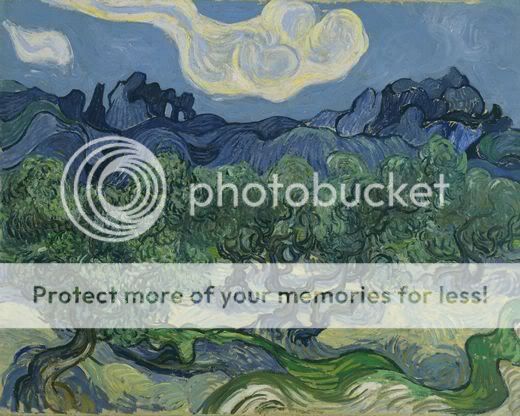

The Olive Trees Vincent Van Gogh

After van Gogh (1853 – 1890) voluntarily entered the asylum at Saint-Rémy in the south of France in the spring of 1889, he wrote his brother Theo: “I did a landscape with olive trees and also a new study of a starry sky.” Later, when the pictures had dried, he sent both of them to Theo in Paris, noting: “The olive trees with the white cloud and the mountains behind, as well as the rise of the moon and the night effect, are exaggerations from the point of view of the general arrangement; the outlines are accentuated as in some old woodcuts.”

Van Gogh’s letters make it clear that he created this particular intense vista of the southern French landscape as a daylight partner to the visionary nocturne of his more famous canvas, The Starry Night. He felt that both pictures showed, in complementary ways, the principles he shared with his fellow painter Paul Gauguin, regarding the freedom of the artist to go beyond “the photographic and silly perfection of some painters” and intensify the experience of color and linear rhythms.

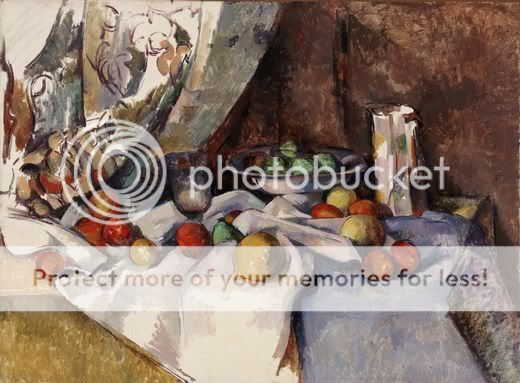

Still Life with Apples Paul Cezanne

Most of the painting of Paul Cezanne (1839 – 1906) are still lifes. These were done in the studio, with simple props; a cloth, some apples, a vase or bowl and, later in his career, plaster sculptures. Cézanne’s still lifes are both traditional and modern. The fruits and objects are readily identifiable, but they have no aroma, no sensual or tactile appeal and no other function other than as passive decorative objects coexisting in the same flat space. They bear no relation to the colorful vegetables of Provence — gorgeous red tomatoes, purple aubergines, and bright green courgettes. In his pursuit of the essence of art, Cézanne had to suppress earthly delights.

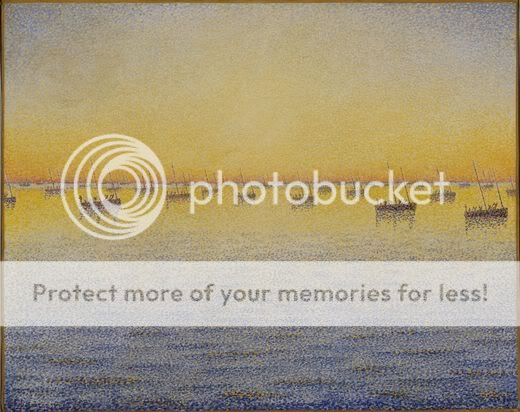

Setting Sun by Paul Signac

Paul Signac (November 11, 1863 – August 15, 1935) was a French neo-impressionist painter who, working with Georges Seurat, helped develop the pointillist style. Paul Victor Jules Signac was born in Paris on November 11, 1863. He followed a course of training in architecture before deciding at the age of 18 to pursue a career as a painter. He sailed around the coasts of Europe, painting the landscapes he encountered. He also painted scenes of cities in France in his later years.

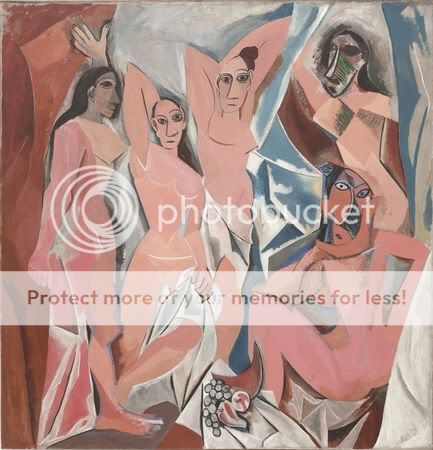

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Paris, Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973)

The faces of the figures at the right are influenced by African masks, which Picasso assumed had functioned as magical protectors against dangerous spirits: this work, he said later, was his “first exorcism painting.” A specific danger he had in mind was life-threatening sexual disease, a source of considerable anxiety in Paris at the time; earlier sketches for the painting more clearly link sexual pleasure to mortality. In its brutal treatment of the body and its clashes of color and style (other sources for this work include ancient Iberian statuary and the work of Paul Cézanne), Les Demoiselles d’Avignon marks a radical break from traditional composition and perspective.

Les Demoiselles d’Avigno is one of the most important works in the genesis of modern art. The painting depicts five naked prostitutes in a brothel; two of them push aside curtains around the space where the other women strike seductive and erotic poses—but their figures are composed of flat, splintered planes rather than rounded volumes, their eyes are lopsided or staring or asymmetrical, and the two women at the right have threatening masks for heads. The space, too, which should recede, comes forward in jagged shards, like broken glass. In the still life at the bottom, a piece of melon slices the air like a scythe.

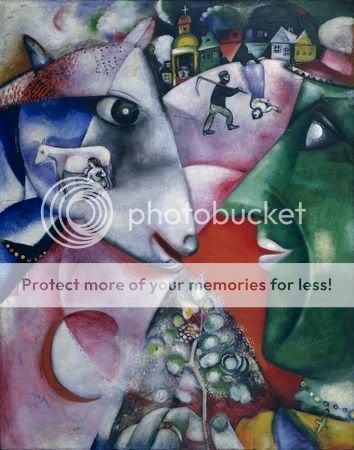

I and the Village, 1911 Marc Chagall

Painted the year after Chagall came to Paris, I and the Village evokes his memories of his native Hasidic community outside Vitebsk. In the village, peasants and animals lived side by side, in a mutual dependence here signified by the line from peasant to cow, connecting their eyes. The peasant’s flowering sprig, symbolically a tree of life, is the reward of their partnership. For Hasids, animals were also humanity’s link to the universe, and the painting’s large circular forms suggest the orbiting sun, moon (in eclipse at the lower left), and earth.

The geometries of I and the Village are inspired by the broken planes of Cubism, but Chagall’s is a personalized version. As a boy he had loved geometry: “Lines, angles, triangles, squares,” he would later recall, “carried me far away to enchanting horizons.” Conversely, in Paris he used a disjunctive geometric structure to carry him back home. Where Cubism was mainly an art of urban avant-garde society, I and the Village is nostalgic and magical, a rural fairy tale: objects jumble together, scale shifts abruptly, and a woman and two houses, at the painting’s top, stand upside-down. “For the Cubists,” Chagall said, “a painting was a surface covered with forms in a certain order. For me a painting is a surface covered with representations of things . . . in which logic and illustration have no importance.”

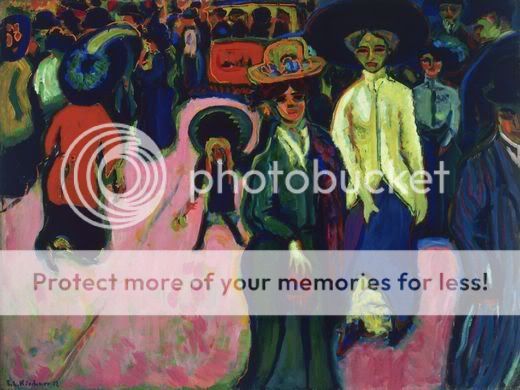

Dresden Street Ernest Ludwig Kirchner, German (1830 – 1938)

Kirchner was a German painter, printmaker and sculptor. He is one of the most important representatives of Expressionism. His pictures of urban life have become the incarnation of the nervously agitated modern state of mind in Europe on the eve of World War I. After 1917, with his depictions of the Swiss mountain landscape of Davos and its inhabitants, he made one of the most important contributions to landscape painting in the 20th century.

Street, Dresden is Kirchner’s bold, discomfiting attempt to render the jarring experience of modern urban bustle. The scene radiates tension. Its packed pedestrians are locked in a constricting space; the plane of the sidewalk, in an unsettlingly intense pink (part of a palette of shrill and clashing colors), slopes steeply upward, and exit to the rear is blocked by a trolley car. The street—Dresden’s fashionable Königstrasse—is crowded, even claustrophobically so, yet everyone seems alone. The women at the right, one clutching her purse, the other her skirt, are holding themselves in, and their faces are expressionless, almost masklike. A little girl is dwarfed by her hat, one in a network of eddying, whorling shapes that entwine and enmesh the human figures.

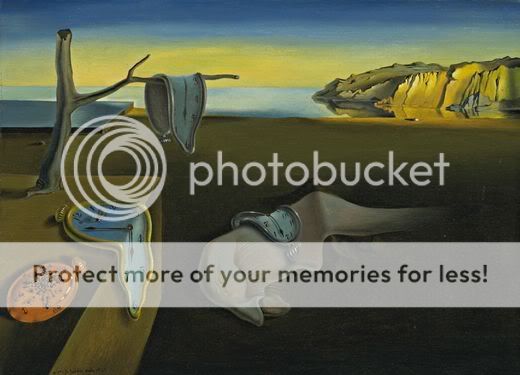

The Persistance of Memory Salvador Dali

Bringing together more than 130 paintings, drawings, scenarios, and films by Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), this exhibition explores the role that cinema played in the artist’s work. Both an inspiration and an outlet for experimentation, film was Dalí’s passion, and cinematic vision became a model for his own work. Collaborations between Dalí and legendary filmmakers are displayed alongside his paintings and other works, illuminating the ways in which ideas, iconography, and pictorial strategies are shared and transformed across mediums. Among the provocative works on display are Un Chien andalou, a film made with Luis Buñuel, which features the notorious, almost unwatchable sequence of an eye being slit by a razor; L’Age d’Or, another collaboration with Buñuel and one of the landmarks of Surrealist film; projects undertaken in Hollywood with Alfred Hitchcock and Walt Disney; and such important paintings as The First Days of Spring and Illumined Pleasures. In conjunction with the gallery exhibition, a series of screenings in the MoMA theaters presents the classic and avant-garde motion pictures Dalí treasured, films on which he collaborated, and examples of his legacy in contemporary cinema.

Un Chien Andalou, 1929 – a film by Salvador Dali

Un Chien Andalou – Part 2

The information I gathered about all the artists on this page were obtained from the official website of The Museum of Modern Art at:http://www.moma.org

12 CommentsChronological Reverse Threaded

|

instrumentalpavilion wrote on Sep 20, ’08

Great place, thanks!

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Sep 20, ’08

It was a wonderful day, and also the exhibit, “Jazz Score” was great too !

|

|

philsgal7759 wrote on Sep 20, ’08

Awesome collection thanks

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Sep 20, ’08

They are doing a Van Gogh exhibit now at the Modern Art Museum called, “The Starry Night”. I’ll have to check it out.

|

|

starfishred wrote on Sep 20, ’08

very very very nice post thanks a lot laurita

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Sep 21, ’08

Thanks for visiting, Heidi !

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Sep 21, ’08

Thanks for visiting, nemo. I hope you enjoyed it.

|

|

forgetmenot525 wrote on Sep 21, ’08

wow……………fantastic post, you managed to get so many different artists and paintings all into one post………wonderful. Love the first one, the Matisse, funny thing is it took me many years to appreciate Matisse, I didn’t like his work at all, njow i really appreciate his skill at making shapes on the canvas, and his use of colour, thanks laurita

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Sep 21, ’08

Loretta, that first painting, the Matisse, they actually had the nerve to hang it in a corner by a stairwell. I was so mad, I should have complained. It should have been in a main exhibit room.

|

Comments

Art Sunday 09/21/08: My Trip to MOMA — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>