POETRY WEDNESDAY 08/13/08: Paradiso by Dante Alighieri

Right: Dante Alighieri painted by Sandro Botticelli (1444-1510). Click to enlarge.

Right: Dante Alighieri painted by Sandro Botticelli (1444-1510). Click to enlarge.

Dante Alighieri, or simply Dante (mid-May to mid-June 1265 -September 13/14, 1321), was an Italian poet from Florence.

His central work, The Divina Commedia (originally called “Commedia” and later called “Divina” (divine) by Boccaccio hence “Divina Commedia”), is considered the greatest literary work composed in the Italian language and a masterpiece of world literature.

In Italian he is known as “the Supreme Poet” (il Sommo Poeta). Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio are also known as “the three fountains” or “the three crowns”. Dante is also called the “Father of the Italian language”. The first biography written on him was by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), who wrote the Trattatello in laude di Dante.The exact date of Dante’s birth is unknown, although it is generally believed to be around 1265.

Not much is known about Dante’s education, and it is presumed he studied at home. It is known that he studied Tuscan poetry, at a time when the Sicilian School (Scuola poetica siciliana), a cultural group from Sicily, was becoming known in Tuscany. His interests brought him to discover the Occitan poetry of the trubadours and the Latin poetry of classical antiquity.

The Divine Comedy describes Dante’s journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Paradise (Paradiso), guided first by the Roman poet Virgil and then by Beatrice, the subject of his love and of another of his works, La Vita Nuova. While the vision of Hell, the Inferno, is vivid for modern readers, the theological niceties presented in the other books require a certain amount of patience and knowledge to appreciate. Purgatorio, the most lyrical and human of the three, also has the most poets in it; Paradiso, the most heavily theological, has the most beautiful and ecstatic mystic passages in which Dante tries to describe what he confesses he is unable to convey (e.g., when Dante looks into the face of God: “all’alta fantasia qui mancò possa” – “at this high moment, ability failed my capacity to describe,” Paradiso, XXXIII, 142).

Dante wrote the Comedy in a new language he called “Italian”, based on the regional dialect of Tuscany, with some elements of Latin and of the other regional dialects. By creating a poem of epic structure and philosophic purpose, he established that the Italian language was suitable for the highest sort of expression. In French, Italian is nicknamed la langue de Dante. Publishing in the vernacular language marked Dante as one of the first (among others such as Geoffrey Chaucer and Giovanni Boccaccio) to break from standards of publishing in only Latin (the languages of liturgy, history, and scholarship in general). This break allowed more literature to be published for a wider audience – setting the stage for greater levels of literacy in the future.

Readers often cannot understand how such a serious work may be called a “comedy”. In Dante’s time, all serious scholarly works were written in Latin (a tradition that would persist for several hundred years more, until the waning years of the Enlightenment) and works written in any other language were assumed to be more trivial in nature. Furthermore, the word “comedy,” in the classical sense, refers to works which reflect belief in an ordered universe, in which events not only tended towards a happy or “amusing” ending, but an ending influenced by a Providential will that orders all things to an ultimate good. By this meaning of the word, the progression of Dante’s pilgrimage from Hell to Paradise is the paradigmatic expression of comedy, since the work begins with the pilgrim’s moral confusion and ends with the vision of God.

After an initial ascension (Canto I), Beatriceguides Dante through the nine celestial spheres of Heaven. These are concentric and spherical, similar to Aristotelian and Ptolemaic cosmology. Dante admits that the vision of heaven he receives is the one that his human eyes permit him to see. Thus, the vision of heaven found in the Cantos is Dante’s own personal vision, ambiguous in its true construction. The addition of a moral dimension means that a soul that has reached Paradise stops at the level applicable to it. Souls are allotted to the point of heaven that fits with their human ability to love God. Thus, there is a heavenly hierarchy. All parts of heaven are accessible to the heavenly soul. That is to say all experience God but there is a hierarchy in the sense that some souls are more spiritually developed than others. This is not determined by time or learning as such but by their proximity to God (how much they allow themselves to experience Him above other things). It must be remembered in Dante’s schema that all souls in Heaven are on some level always in contact with God.

While the structures of the Inferno and Purgatorio were based around different classifications of sin, the structure of the Paradiso is based on the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues.

The Spheres of Heaven

The nine spheres are:

First Sphere. The sphere of the Moon is that of souls who abandoned their vows, and so were deficient in the virtue of fortitude (Cantos II through V). Dante meets Piccarda, sister of Dante’s friend Forese Donati, who died shortly after being forcibly removed from her convent. Beatrice discourses on the freedom of the will, and the inviolability of sacred vows.

Second Sphere. The sphere of Mercury is that of souls who did good out of a desire for fame, but who, being ambitious, were deficient in the virtue of justice (Cantos V through VII). Justinian recounts the history of the Roman Empire. Beatrice explains to Dante the atonement of Christ for the sins of humanity.

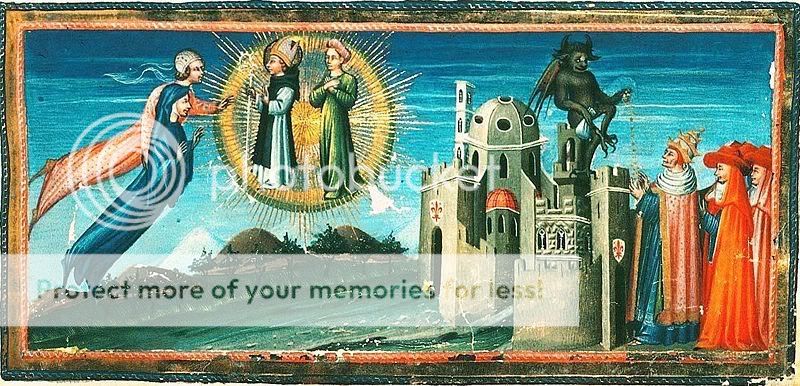

Folquet de Marseilles bemoans the corruption of the Church, in a miniature by Giovanni di Paolo, Paradiso, Canto 9

Third Sphere. The sphere of Venus is that of souls who did good out of love, but were deficient in the virtue of temperance (Cantos VIII and IX). Dante meets Charles Martel of Anjou, who decries those who adopt inappropriate vocations, and Cunizza da Romano. Folquet de Marseilles points out Rahab, the brightest soul among those of this sphere, and condemns the city of Florence for producing that “cursed flower” (the florin) which is responsible for the corruption of the Church.

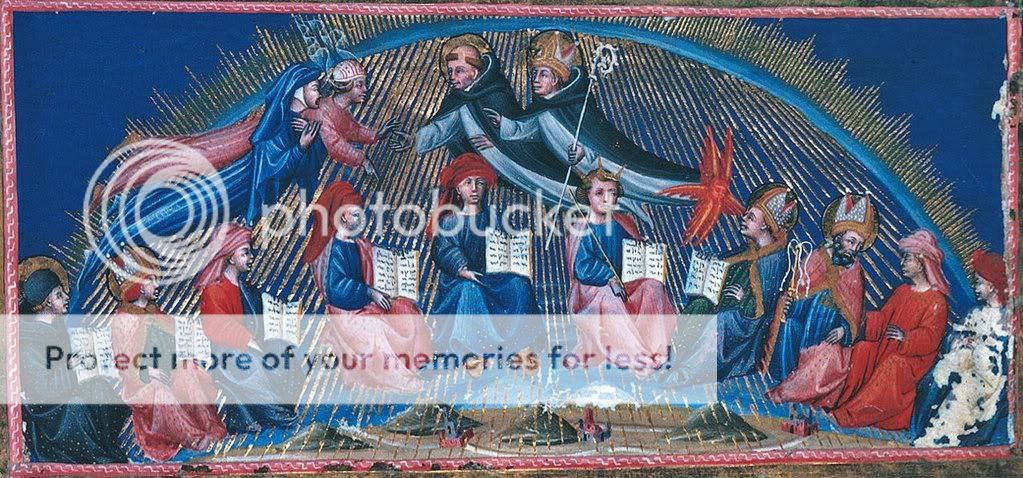

Illustration of Dante’s Paradiso, showing Thomas Aquinas and 11 other teachers of wisdom in the sphere of the Sun, by Giovanni di Paolo (between 1442 and c.1450)

Fourth Sphere. The sphere of the Sun is that of souls of the wise, who embody prudence (Cantos X through XIV). Dante is addressed by St. Thomas Aquinas, who recounts the life of St. Francis of Assisi and laments the corruption of his own Dominican Order. Dante is then met by St. Bonaventure, a Franciscan, who recounts the life of St. Dominic and laments the corruption of the Franciscan Order. The two orders were not always friendly on earth, and having members of one order praising the founder of the other shows the love present in Heaven. Dante arranges the wise into two rings of twelve; his choices of who to include give his assessment of the significant philosophers of medieval times. Finally, Aquinas introduces King Solomon, who answers Dante’s question about the doctrine of the resurrection of the body.

Fifth Sphere. The sphere of Mars is that of souls who fought for Christianity, and who embody fortitude (Cantos XIV through XVIII). The souls in this sphere form an enormous cross. Dante speaks with the soul of his ancestor Cacciaguida, who praises the former virtues of the residents of Florence, recounts the rise and fall of Florentine families and foretells Dante’s exile from Florence, before finally introducing some notable warrior souls (among them Joshua, Roland, Charlemagne, and Godfrey of Bouillon).

Sixth Sphere. The sphere of Jupiter is that of souls who personified justice, something of great concern to Dante (Cantos XVIII through XX). The souls here spell out the Latin for “Love justice, ye that judge the earth,” and then arrange themselves into the shape of an imperial eagle. Present here are David, Hezekiah, Trajan (converted to Christianity according to a medieval legend), Constantine, William II of Sicily, and (Dante is amazed at this) Rhipeus the Trojan, saved by the mercy of God.

Seventh Sphere. The sphere of Saturn is that of the contemplatives, who embody temperance (Cantos XXI and XXII). Dante here meets Peter Damian, and discusses with him monasticism, the doctrine of predestination, and the sad state of the Church. Beatrice, who represents theology, becomes increasingly lovely here, indicating the contemplative’s closer insight into the truth of God.

Eighth Sphere. The sphere of fixed stars is the sphere of the Church Triumphant (Cantos XXII through XXVII). Here, Dante sees visions of Christ and of the Virgin Mary. He is tested on faith by Saint Peter, hope by Saint James, and love by Saint John the Evangelist. Dante justifies his medieval belief in astrology, that the power of the constellations is drawn from God.

Ninth Sphere. The Primum Mobile (“first moved” sphere) is the abode of angels (Cantos XXVII through XXIX). Dante sees God as a point of light surrounded by nine rings of angels, and is told about the creation of the universe.

Paradiso: Canto XXXIII

The Final Vision

by Dante Alighieri

“Thou Virgin Mother, daughter of thy Son,

Humble and high beyond all other creature,

The limit fixed of the eternal counsel,

Thou art the one who such nobility

To human nature gave, that its Creator

Did not disdain to make himself its creature.

Within thy womb rekindled was the love,

By heat of which in the eternal peace

After such wise this flower has germinated.

Here unto us thou art a noonday torch

Of charity, and below there among mortals

Thou art the living fountain-head of hope.

Lady, thou art so great, and so prevailing,

That he who wishes grace, nor runs to thee,

His aspirations without wings would fly.

Not only thy benignity gives succour

To him who asketh it, but oftentimes

Forerunneth of its own accord the asking.

In thee compassion is, in thee is pity,

In thee magnificence; in thee unites

Whate’er of goodness is in any creature.

Now doth this man, who from the lowest depth

Of the universe as far as here has seen

One after one the spiritual lives,

Supplicate thee through grace for so much power

That with his eyes he may uplift himself

Higher towards the uttermost salvation.

And I, who never burned for my own seeing

More than I do for his, all of my prayers

Proffer to thee, and pray they come not short,

That thou wouldst scatter from him every cloud

Of his mortality so with thy prayers,

That the Chief Pleasure be to him displayed.

Still farther do I pray thee, Queen, who canst

Whate’er thou wilt, that sound thou mayst preserve

After so great a vision his affections.

Let thy protection conquer human movements;

See Beatrice and all the blessed ones

My prayers to second clasp their hands to thee!”

The eyes beloved and revered of God,

Fastened upon the speaker, showed to us

How grateful unto her are prayers devout;

Then unto the Eternal Light they turned,

On which it is not credible could be

By any creature bent an eye so clear.

And I, who to the end of all desires

Was now approaching, even as I ought

The ardour of desire within me ended.

Bernard was beckoning unto me, and smiling,

That I should upward look; but I already

Was of my own accord such as he wished;

Because my sight, becoming purified,

Was entering more and more into the ray

Of the High Light which of itself is true.

From that time forward what I saw was greater

Than our discourse, that to such vision yields,

And yields the memory unto such excess.

Even as he is who seeth in a dream,

And after dreaming the imprinted passion

Remains, and to his mind the rest returns not,

Even such am I, for almost utterly

Ceases my vision, and distilleth yet

Within my heart the sweetness born of it;

Even thus the snow is in the sun unsealed,

Even thus upon the wind in the light leaves

Were the soothsayings of the Sibyl lost.

O Light Supreme, that dost so far uplift thee

From the conceits of mortals, to my mind

Of what thou didst appear re-lend a little,

And make my tongue of so great puissance,

That but a single sparkle of thy glory

It may bequeath unto the future people;

For by returning to my memory somewhat,

And by a little sounding in these verses,

More of thy victory shall be conceived!

I think the keenness of the living ray

Which I endured would have bewildered me,

If but mine eyes had been averted from it;

And I remember that I was more bold

On this account to bear, so that I joined

My aspect with the Glory Infinite.

O grace abundant, by which I presumed

To fix my sight upon the Light Eternal,

So that the seeing I consumed therein!

I saw that in its depth far down is lying

Bound up with love together in one volume,

What through the universe in leaves is scattered;

Substance, and accident, and their operations,

All interfused together in such wise

That what I speak of is one simple light.

The universal fashion of this knot

Methinks I saw, since more abundantly

In saying this I feel that I rejoice.

One moment is more lethargy to me,

Than five and twenty centuries to the emprise

That startled Neptune with the shade of Argo!

My mind in this wise wholly in suspense,

Steadfast, immovable, attentive gazed,

And evermore with gazing grew enkindled.

In presence of that light one such becomes,

That to withdraw therefrom for other prospect

It is impossible he e’er consent;

Because the good, which object is of will,

Is gathered all in this, and out of it

That is defective which is perfect there.

Shorter henceforward will my language fall

Of what I yet remember, than an infant’s

Who still his tongue doth moisten at the breast.

Not because more than one unmingled semblance

Was in the living light on which I looked,

For it is always what it was before;

But through the sight, that fortified itself

In me by looking, one appearance only

To me was ever changing as I changed.

Within the deep and luminous subsistence

Of the High Light appeared to me three circles,

Of threefold colour and of one dimension,

And by the second seemed the first reflected

As Iris is by Iris, and the third

Seemed fire that equally from both is breathed.

O how all speech is feeble and falls short

Of my conceit, and this to what I saw

Is such, ’tis not enough to call it little!

O Light Eterne, sole in thyself that dwellest,

Sole knowest thyself, and, known unto thyself

And knowing, lovest and smilest on thyself!

That circulation, which being thus conceived

Appeared in thee as a reflected light,

When somewhat contemplated by mine eyes,

Within itself, of its own very colour

Seemed to me painted with our effigy,

Wherefore my sight was all absorbed therein.

As the geometrician, who endeavours

To square the circle, and discovers not,

By taking thought, the principle he wants,

Even such was I at that new apparition;

I wished to see how the image to the circle

Conformed itself, and how it there finds place;

But my own wings were not enough for this,

Had it not been that then my mind there smote

A flash of lightning, wherein came its wish.

Here vigour failed the lofty fantasy:

But now was turning my desire and will,

Even as a wheel that equally is moved,

The Love which moves the sun and the other stars.

Illuminations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

by Giovanni di Paolo (15th cent)

From the Primum Mobile, Dante ascends to a region beyond physical existence, called the Empyrean (Cantos XXX through XXXIII).

Here the souls of all the believers form the petals of an enormous rose. Beatrice leaves Dante with Saint Bernard, because theology has here reached its limits. Saint Bernard prays to Mary on behalf of Dante.

Finally, Dante comes face-to-face with God Himself, and is granted understanding of the Divine and of human nature. His vision is improved beyond that of human comprehension. God appears as three equally large circles within each other representing the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit with the essence of each part of God, separate yet one. The book ends with Dante trying to understand how the circles fit together, how the Son is separate yet one with the Father but as Dante put it “that was not a flight for my wings” and the vision of God becomes equally inimitable and inexplicable that no word or intellectual exercise can come close to explaining what he saw.

Dante’s soul, through God’s absolute love, experiences a unification with itself and all things “but already my desire and my will were being turned like a wheel, all at one speed by the Love that turns the sun and all the other stars”.

La Conferma Della Regola (Gregorian Chant of Italian Monastery) – Capitanata

*portions of this post were provided with the assistance of Wikipedia.

Click here to return toSans Souci, our poetess hostess with the mostess, who is hosting Poetry Wednesday.

|

starfishred wrote on Aug 12, ’08

oh my had to spend a whole quarter on this in college how I used to wish it would go away hehehe but very good presentation and tribute to a wonderful piece of literature-

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 12, ’08

I know what you mean, Heidi, but I find when we are older and not under pressure from school to learn that we come to appreciate a masterpiece as this.

|

|

starfishred wrote on Aug 12, ’08

lauritasita said

Deffinatly we look at things from a whole different point of view and then we can appreciate it to

|

|

sanssouciblogs wrote on Aug 12, ’08

I know what Heidi is saying! Whew! I didn’t appreciate it then–I can appreciate it now but I can’t even internalize it all. Certainly Dante was one deep fellow and a genius. In those days, everything was religion, church, Christ. Poets, artists, craftsmen devoted their lives to this and all that goes with it.

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 12, ’08

I found this poetry in a book I found in an antique store. It mostly focused on the artwork by Giovanni Di Paolo, reflecting his interpretation of Dante’s poems. You could say I taught myself about Dante this week !

|

|

vickiecollins wrote on Aug 12, ’08

I love the artwork…I hate to admit this but the poetry is a bit hard for me to follow.

http://vickiecollins.multiply.com/journal/item/439/Poetry_Wednesday_Works_Hard_for_Her_Money |

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 12, ’08, edited on Aug 12, ’08

Vickie, Thanks for visiting. The Paradiso is acutally only a section of a The Divine Comedy, but basically Dante is describing face-to-face contact with God. He appears as three equally large circles (as in the painting with the last paragraph) within each other representing the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit with the essence of each part of God, separate yet one. “The book ends with Dante trying to understand how the circles fit together, how the Son is separate yet one with the Father but as Dante put it “that was not a flight for my wings” and the vision of God becomes equally inimitable and inexplicable that no word or intellectual exercise can come close to explaining what he saw.”

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 12, ’08

It just goes to show you how school can make you not apprectiate something beautiful until years later when you are now an adult, and have the time (and hopefully the patience) to understand it.

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 12, ’08

Hi poetricjay, I don’t really remember what I studied in school as far as poetry. I found this art book of the work of Giovanni di Paolo illustrating this poem and was curious as to what the poem was like, so I posted them together. I thought they were beautiful together.

|

|

sweetpotatoqueen wrote on Aug 13, ’08

This work is something to be savored and pondered upon for it’s beauty of the universe and the wonders of love. Timeless and always thought provoking ! The music is wonderful and perfect for this ancient writing. I’ll be back to sip of this later…it’s too grand to take in one gulp! Thank you!

|

|

mindsnomad wrote on Aug 13, ’08

Thank you so much for the information here. I never studied Dante (its one of the things that we dont study unless we are literature majors.) So this is new to me and its a lot of thinking to do.:)

|

|

jemimapuddleduck wrote on Aug 13, ’08

i have always love monkish music, thank you

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 13, ’08

I think I remember parts of this in high school, but I’m glad I have more time as an adult to get more spiritual meaning out of it.

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 13, ’08

Thanks for visiting, rooanns. This poetry is not the easiest to understand. I’ve already spent a long time mulling over it, but from what I have read is that Dante is describing what it’s like to come into contact with God. This poem is the last of three sections.

|

|

bostonsdandd wrote on Aug 14, ’08

very nice post. I can see how the question of finding out the truth would bother most. It IS a confusing subject and he did a wonderful job getting that across, in my opinion. I really like how he referred to Mary at the beginning, “the daughter of your Son.” LOL In truth that is true because the three ARE one ;o).

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 14, ’08

Thank you for your comment, Lori. I realize this was a complex post to do, and requires much patience and concentration to appreciate it.

|

|

philsgal7759 wrote on Aug 16, ’08

Thanks for this I must return when I am more awake but it is very insightful

|

|

skeezicks1957 wrote on Aug 16, ’08

at the multiply book group that I enjoy, http://booksamultiplyin.multiply.com/ , the book selection for November is a modern novel called “The Dante Club”. I think the information you have posted here will be great back ground for me. So I will be back to study this closer. My intro college literature class did not cover this work.

|

|

lauritasita wrote on Aug 16, ’08

Wow skeezicks, I hope my post helps you ! Feel free to use any information here that you need.

|

I know what you mean, Heidi, but I find when we are older and not under pressure from school to learn that we come to appreciate a masterpiece as this.

I know what you mean, Heidi, but I find when we are older and not under pressure from school to learn that we come to appreciate a masterpiece as this.

Comments

POETRY WEDNESDAY 08/13/08: Paradiso by Dante Alighieri — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>